January 4, 2010

LA JOLLA, CA—Like a spotlight that illuminates an otherwise dark scene, attention brings to mind specific details of our environment while shutting others out. A new study by researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies shows that the superior colliculus, a brain structure that primarily had been known for its role in the control of eye and head movements, is crucial for moving the mind’s spotlight.

Their findings, published in the Dec. 20, 2009, issue of the journal Nature Neuroscience, add new insight to our understanding of how attention is controlled by the brain. The results are closely related to a neurological disorder known as the neglect syndrome, and they may also shed light on the origins of other disorders associated with chronic attention problems, such as autism or attention deficit disorder.

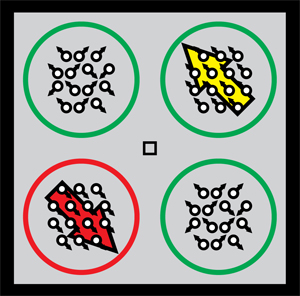

During the motion discrimination task the test subjects had to fixate their gaze at the square in the middle while reporting the direction of movement in the red circle.

Image: Courtesy of Lee Lovejoy, Salk Institute for Biological Studies

“Our ability to survive in the world depends critically on our ability to respond to relevant pieces of information and ignore others,” explains graduate student and first author Lee Lovejoy, who conducted the study together with Richard Krauzlis, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Salk’s Systems Neurobiology Laboratory. “Our work shows that the superior colliculus is involved in the selection of things we will respond to, either by looking at them or by thinking about them.”

As we focus on specific details in our environment, we usually shift our gaze along with our attention. “We often look directly at attended objects and the superior colliculus is a major component of the motor circuits that control how we orient our eyes and head toward something seen or heard,” says Krauzlis.

But humans and other primates are particularly adept at looking at one thing while paying attention to another. As social beings, they very often have to process visual information without looking directly at each other, which could be interpreted as a threat. This requires the ability to attend covertly.

It had been known that the superior colliculus plays a role in deciding how to orient the eyes and head to interesting objects in the environment. But it was not clear whether it also had a say in covert attention.

In their current study, the Salk researchers specifically asked whether the superior colliculus is necessary for covert attention. To tease out the superior colliculus’ role in covert attention, they designed a motion discrimination task that distinguished between control of gaze and control of attention.

The superior colliculus contains a topographic map of the visual space around us, just as conventional maps mirror geographical areas. Lovejoy and Krauzlis exploited this property to temporarily inactivate the part of the superior colliculus corresponding to the location of the cued stimulus on the computer screen. No longer aware of the relevant information right in front of them the subjects instead based all of their decision about the stimulus’ movement on irrelevant information found elsewhere on the screen.

“The result is very similar to what happens in patients with neglect syndrome,” explains Lovejoy, who is also a student in the Medical Scientist Training Program at UC San Diego. “Up to a half of acute right-hemisphere stroke patients demonstrate signs of spatial neglect, failing to be aware of objects or people to their left in extra-personal space.”

“Our results show that deciding what to attend to and what to ignore is not just accomplished with the neocortex and thalamus, but also depends on phylogenetically older structures in the brainstem,” says Krauzlis. “Understanding how these newer and older parts of the circuit interact may be crucial for understanding what goes wrong in disorders of attention.”

The work was funded in part by the Simons Foundation, the Institute for Neural Computation and an Aginsky Scholar Award.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu