April 15, 2010

La Jolla, CA—A multicellular green alga, Volvox carteri, may have finally unlocked the secrets behind the evolution of different sexes. A team led by researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies has shown that the genetic region that determines sex in Volvox has changed dramatically relative to that of the closely related unicellular alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.

Their findings, which will be published in the April 16th issue of the journal Science, provide the first empirical support for a model of the evolution of two different sexes whereby expansion of a sex-determining region creates genetic diversity followed by genes taking on new functions related to the production of male and female reproductive cells termed gametes.

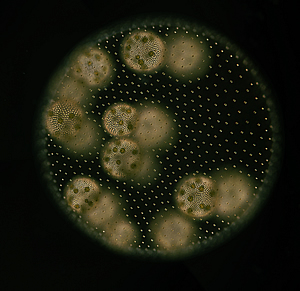

Vegetative female colony. Volvox carteri forms spherical colonies, which are composed of 2,000 to 4,000 individual cells embedded in an extracellular matrix. During non-sexual reproduction, so-called gonidia in both male and female (pictured) colonies produce juvenile colonies through repeated division.

Image: Courtesy of the Umen laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Research

“Until now, sex-determining chromosomes had generally been viewed as regions of decay, steadily losing genes that are not involved in sexual reproduction,” explains James Umen, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory at the Salk Institute, who led the team conducting the study. “Our study shows the opposite-that such regions can expand and generate new genetic material much more rapidly than the rest of the genome.”

Most multicellular organisms such as plants and animals have two distinct sexes with females producing large immotile eggs and males producing small motile sperm. While unicellular organisms can also reproduce sexually, the two sexes of single-celled species are typically indistinguishable from each other and are thought to represent an ancestral or early evolutionary state. However, the large distances that separate plants or animals from their closest unicellular relatives have precluded understanding the evolutionary transition to male-female dimorphism.

“In unicellular organisms like Chlamydomonas, the gametes look the same. In contrast, multicellular organisms, including Volvox, produce eggs and sperm-they are distinctly male and female. Yet no one really has any idea how the evolution of males and females occurs or what genetic changes were required to achieve it,” explains Umen.

Although the genomes of Chlamydomonas and Volvox are similar in most ways, there is one glaring exception that provided the Salk researchers with an entrée into the origin of male and female sexes-the so-called mating locus that functions in much the same way as human X and Y chromosomes to determine gender.

When Umen and his colleagues examined the mating locus genes in Chlamydomonas and Volvox they found that they shared some of the same genes, as you would expect from closely related species. However, Volvox also now possessed a surprising variety of new genes that were added to its expanded mating locus, and expression of many of these genes had come under the control of the male or female differentiation programs.

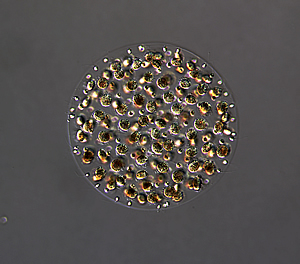

Sexual male colony. During sexual reproduction, male Volvox carteri colonies produce sperm packets each containing 64 or 128 sperm cells. After their release individual sperm packets swim as unit until they reach a female spheroid where they dissociate prior to entry of fertilization of eggs.

Image: Courtesy of the Umen laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Research

“We found that the Volvox mating locus is about five times bigger than that of Chlamydomonas,” says postdoctoral researcher and co-first author Patrick Ferris, Ph.D. “We wanted to understand the evolutionary basis of this. How did it happen? And where did these new genes come from?”

To trace the origin of the added genes, the team looked to see if they could also find them in Chlamydomonas. “We found that although some of the mating locus genes in Volvox are completely new, many of them have counterparts in Chlamydomonas that are near the mating locus,” explains co-first author Bradley Olson, Ph.D. “So Volvox has taken these genes that initially had nothing to do with sex, incorporated them into its mating locus, and started using some of them in its sexual reproductive cycle.”

The team is now studying these new mating locus genes to understand their individual roles in sex determination and sexual development.

They have already identified a Volvox mating locus gene named MAT3 that appears to have evolved a new role in sexual differentiation. MAT3 is related to a human gene called the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor that controls cell division and is frequently mutated in cancer cells. In Volvox, MAT3 probably has a role in controlling cell division as it does in animals and plants, but has also acquired intriguing gender-specific differences in its sequence and expression pattern that correlate with differences in male/female reproductive development. Umen’s laboratory is following up on this finding to determine the newly evolved role of MAT3 in Volvox gender specification.

“This study shows that Volvox and its relatives are a powerful model in which to study the evolution of sex,” says Umen. “It provides us with a system in which we can retrace evolutionary history to ask questions about the origin of gender and other traits that are difficult to approach in groups such as plants and animals.”

The team is also working with collaborators to examine the mating locus of an evolutionary intermediate between Chlamydomonas and Volvox called Gonium, which has between four and 16 cells. “Gonium allows us to look at the evolutionary steps between Chlamydomonas and Volvox to better understand how the evolutionary process happened,” says Ferris.

In addition to Ferris, Olson and Umen, contributors to this work were Peter L. De Hoff, Ph.D., and Sa Geng, Ph.D. at the Salk Institute; Stephen Douglass, David Casero and Matteo Pellegrini at UCLA; Simon Prochnik at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI), Rhitu Rai at the Salk Institute and the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi; Jane Grimwood and Jeremy Schmutz at Hudson Alpha Institute for Biotechnology, Alabama; Ichiro Nishii at Nara Women’s University, Nara, Japan; and Takashi Hamaji and Hisayoshi Nozaki at the University of Tokyo, Japan.

-Claire Attwooll

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu