May 12, 2011

Findings may suggest novel ways to treat metabolic conditions such as obesity and type II diabetes.

Findings may suggest novel ways to treat metabolic conditions such as obesity and type II diabetes.

LA JOLLA, CA—By virtue of having survived, all animals-from flies to man-share a common expertise. All can distinguish times of plenty from famine and adjust their metabolism or behavior accordingly. Failure to do so signals either extinction or disease.

A collaborative effort by investigators at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies recently revealed just how similarly mammals and insects make critical metabolic adjustments when food availability changes, either due to environmental catastrophe or everyday changes in sleep/wake cycles. Those findings may suggest novel ways to treat metabolic conditions such as obesity and type II diabetes.

In a study published in the May 13, 2011, issue of Cell, co-investigators Marc Montminy, M.D., Ph.D, professor in the Clayton Foundation Laboratories for Peptide Biology, and John Thomas, Ph.D., professor in the Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, use the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster to show that activation of a factor called SIK3 by insulin dampens a well-characterized pathway promoting fat breakdown, providing a molecular link between glucose metabolism and lipid storage.

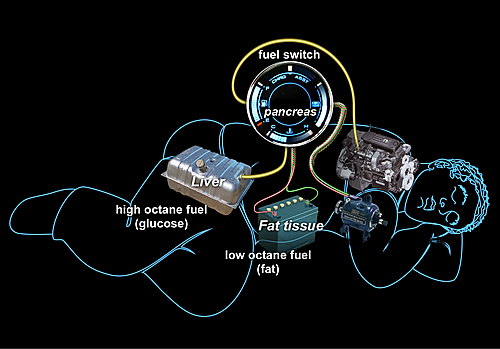

“The metabolic system is like a hybrid car. In the daytime we use glucose as high octane fuel, but at night we switch to the battery, which in this case is stored fat,” says Montminy. “This new study shows how SIK3 promotes lipid storage during daytime feeding hours by blocking fat breakdown programs that normally only function during night-time fasting periods.”

The metabolic system functions like a hybrid car. In the daytime we use glucose as high octane fuel, but at night we switch to the battery, which in this case is stored fat.

Image: Courtesy of Dr. Marc Montminy and Jamie Simon, Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

During fasting, a group of fat-busting enzymes, called lipases, trigger the flow of energy from the fly’s low-power battery fat pack to different organs in the body. These lipases are turned on by a genetic switch, called FOXO, part of the central transmission for fasting metabolism. When the flies eat food, SIK3 shuts off the FOXO switch, which both cuts off the battery’s energy stream by silencing the fat-busting enzymes and allowing the “fat pack” to recharge its batteries.

Having teamed up previously to analyze pathways regulating glucose availability, Montminy, an expert in metabolism, and Thomas, a fly geneticist, focused on SIK3 in part because it is expressed in the fly fat body-a structure equivalent to mammalian adipose tissue and liver-but primarily because it is the Drosophila counterpart of a mammalian liver enzyme that antagonizes fat breakdown.

In experiments led by Biao Wang, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in the Montminy lab and the paper’s first author, the team mutated the Drosophila SIK3 gene, thereby disabling it, and monitored changes in fat metabolism. Mutant flies showed abnormally meager fat stores in the fat body and rapidly starved to death when deprived of food. “A normal fly can store enough fat to survive that period of food deprivation,” says Thomas. “Flies in the wild lacking SIK3 would not make it from one feeding to the next.”

That lack of fat was explained in part by the team’s observation that SIK3 indirectly represses expression of a fat-burning enzyme active only in times of starvation. But the group immediately suspected that SIK3 was antagonizing a much bigger metabolic fish, namely a well-characterized “master regulator” known as FOXO, which in many organisms works in the nucleus to switch on genes that promote fat burning in times of nutrient deprivation.

Unexpectedly, SIK3 does not control the FOXO switch directly. Rather, much like a runner in a relay race, the SIK3 enzyme had to pass the baton to another enzyme called HDAC4, which in turn regulates FOXO.

“The complexity of this molecular machine likely reflects its importance in determining when the fat batteries should be turned on or off,” says Montminy. “Indeed, perhaps the best argument for the importance of a group of molecules is that you see them doing the same thing over and over again in different organisms.”

The investigators found that the SIK3/HDAC4/FOXO machine they had characterized in the fruitfly also controls the metabolic hybrid engine in mice. There, disabling one of these molecules in liver also disrupted the metabolic switch from fasting to feeding.

Ease of genetic manipulation makes flies a popular model organism for biological research. But ease was not the primary motivator of these studies. “Virtually all important components of the insulin pathway are conserved in flies and mammals,” says Montminy. “Numerous human disease genes are expressed in Drosophila, and you can even mimic certain aspects of diabetes in fly models as well.”

Thomas agrees, suggesting that metabolic similarities between flies and mammals exemplify mother nature’s reluctance to improve on a good thing, especially when that good thing determines life or death. “The fact that these same pathways are used wholesale in flies and humans is quite striking,” says Thomas. “A fly has to regulate its metabolism just like a human—if you create something during evolution that works well, it’s likely going to remain conserved.”

Unraveling SIK3/HDAC4/FOXO regulatory activity puts, as Thomas says, “more pharmacological possibilities on the table” in treating metabolic disease, an opinion echoed by Montminy.

“Currently, we have over 20 million people with type 2 diabetes and close to 60 million with insulin resistance,” says Montminy. “This is a huge problem tied to obesity. Finding a way to curb obesity will essentially require consideration of both environmental and genetic factors. The human counterparts of HDAC4 and SIK3 may be mutated in ways that make them work less effectively and enhance our proclivity to become obese.”

Other contributors to the work include Noel Moya and Wolfgang H. Fischer of Salk’s Peptide Biology Laboratory; Reuben J. Shaw and Maria M. Mihaylova of Salk’s Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory; and John R. Yates III, Sherry Niessen and Heather Hoover of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla.

Support for the work was provided by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Diabetes Association, The Kieckhefer Foundation, The Clayton Foundation for Medical Research, and The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

The Center for Nutritional Genomics was established in 2008 with a grant from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust to specifically study fundamental mechanisms underlying the development and treatment of diabetes and metabolic disease.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu