October 19, 2012

Stem cell study may help to unravel how a genetic mutation leads to Parkinson's symptoms

Stem cell study may help to unravel how a genetic mutation leads to Parkinson's symptoms

LA JOLLA, CA—By reprogramming skin cells from Parkinson’s disease patients with a known genetic mutation, researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have identified damage to neural stem cells as a powerful player in the disease. The findings, reported online October 17, 2013 in Nature, may lead to new ways to diagnose and treat the disease.

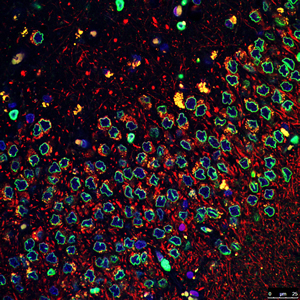

The scientists found that a common mutation to a gene that produce the enzyme LRRK2, which is responsible for both familial and sporadic cases of Parkinson’s disease, deforms the membrane surrounding the nucleus of a neural stem cell. Damaging the nuclear architecture leads to destruction of these powerful cells, as well as their decreased ability to spawn functional neurons, such as the ones that respond to dopamine.

The Salk researchers found that a common genetic mutation involved in Parkinson’s disease deforms the membranes (green) surrounding the nuclei (blue) of neural stem cells. The discovery may lead to new ways to diagnose and treat the disease.

Image: Courtesy of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The researchers checked their laboratory findings with brain samples from Parkinson’s disease patients and found the same nuclear envelope impairment.

“This discovery helps explain how Parkinson’s disease, which has been traditionally associated with loss of neurons that produce dopamine and subsequent motor impairment, could lead to locomotor dysfunction and other common non-motor manifestations, such as depression and anxiety,” says Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in Salk’s Gene Expression Laboratory, who led the research team. “Similarly, current clinical trials explore the possibility of neural stem cell transplantation to compensate for dopamine deficits. Our work provides the platform for similar trials by using patient-specific corrected cells. It identifies degeneration of the nucleus as a previously unknown player in Parkinson’s.”

Although the researchers say that they don’t yet know whether these nuclear aberrations cause Parkinson’s disease or are a consequence of it, they say the discovery could offer clues about potential new therapeutic approaches.

For example, they were able to use targeted gene-editing technologies to correct the mutation in patient’s nuclear stem cells. This genetic correction repaired the disorganization of the nuclear envelope, and improved overall survival and functioning of the neural stem cells.

They were also able to chemically inhibit damage to the nucleus, producing the same results seen with genetic correction. “This opens the door for drug treatment of Parkinson’s disease patients who have this genetic mutation,” says Belmonte.

The new finding may also help clinicians better diagnose this form of Parkinson’s disease, he adds. “Due to the striking appearance in patient samples, nuclear deformation parameters could add to the pool of diagnostic features for Parkinson’s disease,” he says.

The research team, which included scientists from China, Spain, and the University of California, San Diego, and Scripps Research Institute, made their discoveries using human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These cells are similar to natural stem cells, such as embryonic stem cells, except that they are derived from adult cells. While generation of these cells has raised expectations within the biomedical community due to their transplant potential—the idea that they could morph into tissue that needs to be replaced—they also provide exceptional research opportunities, says Belmonte.

“We can model disease using these cells in ways that are not possible using traditional research methods, such as established cell lines, primary cultures and animal models,” he says.

From left: Research associate Guanghui Liu, Professor Juan Carols Izpisua Belmonte, and Keiichiro Suzuki, research associate.

Image: Courtesy of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

In this study, the researchers used skin fibroblast cells taken from Parkinson’s disease patients who have the LRRK2 mutation, and they reprogrammed them to iPSC stem cells and developed them into neural stem cells.

Then, by using an approach to model what happens when these neural stem cells aged, they found that older Parkinson disease neural stem cells increasingly displayed deformed nuclear envelopes and nuclear architecture. “This means that, over time, the LRRK2 mutation affects the nucleus of neural stem cells, hampering both their survival and their ability to produce neurons,” Belmonte says.

“It is the first time to our knowledge that human neural stem cells have been shown to be affected during Parkinson’s pathology due to aberrant LRRK2,” he says. “Before development of these reprogramming technologies, studies on human neural stem cells were elusive because they needed to be isolated directly from the brain.”

Belmonte speculates that the dysfunctional neural stem cell pools that result from the LRRK2 mutation might contribute to other health issues associated with this form of Parkinson’s disease, such as depression, anxiety and the inability to detect smells.

Finally, the study shows that these reprogramming technologies are very useful for modeling disease as well as dysfunction caused by aging, Belmonte says.

Other researchers on the study were: Guang-Hui Liu, Jing Qu, Keiichiro Suzuki, Emmanuel Nivet, Mo Li, Nuria Montserrat, Fei Yi. Xiuling Xu, Sergio Ruiz, Weiqi Zhang, Bing Ren, Ulrich Wagner, Audrey Kim, Ying Li, April Goebl, Jessica Kim, Rupa Devi Soligalla, Ilir Dubova, James Thompson, John Yates III, Concepcion Rodriguez Esteban, and Ignacio Sancho-Martinez.

The research was supported by Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, Sanofi, The California Institute of Regenerative Medicine, Ellison Medical Foundation and Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, MINECO and Fundacion Cellex.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

JOURNAL

Nature

AUTHORS

Guang-Hui Liu, Jing Qu, Keiichiro Suzuki, Emmanuel Nivet, Mo Li, Nuria Montserrat , Fei Yi, Xiuling Xu, Sergio Ruiz, Weiqi Zhang, Bing Ren, Ulrich Wagner, Audrey Kim, Ying Li, April Goebl, Jessica Kim, Rupa Devi Soligalla, Ilir Dubova, James Thompson, John Yates III , Concepcion Rodriguez Esteban, Ignacio Sancho-Martinez, Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu