January 30, 2011

LA JOLLA, CA—Among stem cell biologists there are few better-known proteins than nestin, whose very presence in an immature cell identifies it as a “stem cell,” such as a neural stem cell. As helpful as this is to researchers, until now no one knew which purpose nestin serves in a cell.

In a study published in the Jan. 30, 2011, advance online edition of Nature Neuroscience, Salk Institute of Biological Studies investigators led by Kuo-Fen Lee, PhD., show that nestin has reason for being in a completely different cell type—muscle tissue. There, it regulates formation of the so-called neuromuscular junction, the contact point between muscle cells and “their” motor neurons.

Knowing this not only deepens our understanding of signaling mechanisms connecting brain to muscle, but could aid future attempts to strengthen those connections in cases of neuromuscular disease or spinal cord injury.

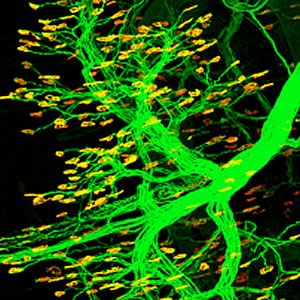

Nestin, a well-known stem cell marker, regulates the formation of neuromuscular junctions (shown in yellow), the contact points between muscles cells and “their” motor neurons (shown in green).

Image: Courtesy of Dr. Jiefei Yang, Salk Institute for Biological Studies

“Nestin was a very well known molecule but no one knew what it did in vivo,” says Lee, a professor in the Clayton Foundation Laboratories for Peptide Biology. “Ours is the first study to show that it actually has a physiological function.”

Previously, researchers knew that as the neuromuscular junction formed in a developing embryo, so-called positive factors cemented connections between incoming nerve fibers and dense clusters of neurotransmitter receptors facing them on muscle fibers. However, in a 2005 Neuron paper Lee defined a counterbalancing factor—the protein cdk5—that whisked away, or dispersed, superfluous muscle receptors lying outside the contact zone, or synapse, so only the most efficient connections were maintained.

The current study addresses how cdk5, which catalytically adds chemical phosphate groups to target proteins, eliminates useless “extrasynaptic” connections. Reasoning that cdk5 must act by chemically modifying a second protein, Jiefei Yang, PhD., a post-doctoral fellow in the Lee lab and the current study’s first author, took on the task of finding its accomplice.

He began by eliminating prime suspects in the plethora of proteins found on the muscle side of the synapse. “At the beginning it was like shooting in the dark because cdk5 has so many potential targets at the neuromuscular junction,” says Yang. After eliminating the obvious candidates, the team finally considered nestin, based on evidence that cdk5 can phosphorylate nestin in some tissues.

To analyze nestin, the group employed mice in which the positive, synapse-stabilizing factor—known as agrin—had been genetically eliminated. As predicted, microscopic examination of diaphragm muscle tissue in agrin mutant mice showed a complete loss of dense receptor clusters that would mark a mature synapse, meaning that without the agrin “cement,” synapse-dispersing activity had swept away the clusters.

However, when agrin mutant mice were administered an RNA reagent that literally knocks out nestin expression, the group made a dramatic finding: the pattern of receptor clusters on diaphragm muscle reappeared, reminiscent of synapses of a normal mouse—meaning that getting rid of nestin allows synapses to proceed even in the absence of the stabilizing glue.

“This in vivo experiment represents a critical genetic finding,” explains Lee. “Later, we determined that nestin’s basic function is to recruit cdk5 and its co-activators to the muscle membrane, leading to cdk5 activation and initiating the dispersion process.” Additional experiments confirmed that nestin is expressed on the muscle side of the neuromuscular junction, in other words, in the “right” place, and that nestin phosphorylation is required for its newfound function.

Lee believes that information revealed by the study could enhance development of tissue replacement therapies. “Currently, in efforts to devise therapies for motor neuron disease or spinal cord injury there is a lot of focus is on how to make neurons survive,” he says. “That is important, but we also need to know how to properly form a synapse. If we cannot, the neuromuscular junction won’t function correctly.”

Yang, who studied animal models of motor neuron disease while a graduate student at USC, agrees. “One long-term goal of this study is to identify ways to inhibit cdk5/nestin,” he says. “That could slow synapse deterioration in neuromuscular junction diseases, such as ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) or spinal motor atrophy, in which you have an imbalance of positive and negative signals. One approach is to boost positive signaling, but another is to inhibit negative signaling in an effort to slow disease progression.”

Other authors of the study include Bertha Dominguez, Fred de Winter, and Thomas Gould in the Lee lab, and John Eriksson at Åbo Akademi University in Turku, Finland.

Support for the work came from the National Institutes of Health, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and the Research Institute of the Åbo Akademi University.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu