September 22, 2011

Salk Institute researchers have built artificially enhanced bacteria capable of producing new kinds of synthetic chemicals

Salk Institute researchers have built artificially enhanced bacteria capable of producing new kinds of synthetic chemicals

La Jolla—A strain of genetically enhanced bacteria developed by researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies may pave the way for new synthetic drugs and new ways of manufacturing medicines and biofuels, according to a paper published September 18 in Nature Chemical Biology.

For the first time, the scientists were able to create bacteria capable of effectively incorporating “unnatural” amino acids – artificial additions to the 20 naturally occurring amino acids used as biological building blocks – into proteins at multiple sites. This ability may provide a powerful new tool for the study of biological processes and for engineering bacteria that produce new types of synthetic chemicals.

“This provides us with a lot more room to think about what we can do with protein synthesis,” said Lei Wang, assistant professor in Salk’s Chemical Biology and Proteomics Laboratory and holder of the Frederick B. Rentschler Developmental Chair. “It opens up new possibilities, from creating drugs that last longer in the blood stream to manufacturing chemicals in a more environmentally friendly manner.”

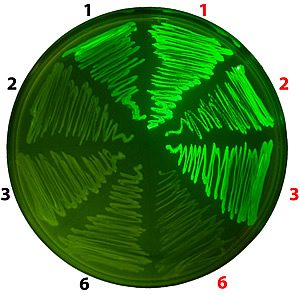

These bacterial smears show common E. coli strains that allow unnatural amino acid (Uaas) incorporation at one site only (left side), and an engineered strain that enables the incorporation of Uaas at multiple sites simultaneously (right side).

The glow indicates the bacteria are producing full-length proteins with Uaas incorporated at different numbers of sites (as indicated by the surrounding numbers), a necessary step for their potential use in the production of new drugs and biofuels.

Image: Courtesy of Salk Institute for Biological Studies

In 2001, Wang and his colleagues were the first to create bacteria that incorporated unnatural amino acids (Uaas) into proteins, and, in 2007, they first used the technique in mammalian cells. They did this by creating an “expanded genetic code,” overriding the genetic code of the cells and instructing them to use the artificial amino acids in the construction of proteins.

The addition of Uaas changes the chemical properties of proteins, promising new ways to use proteins in research, drug development and chemical manufacturing.

For instance, Wang and his colleagues have inserted Uaas that will glow under a microscope when exposed to certain colors of light. Because proteins serve as the basis for a wide range of cellular functions, the ability to visualize this machinery operating in live cells and in real time helps scientists decipher a wide range of biological mechanisms, including those involved in the development of disease and aging.

Genetically modified bacteria are already used for producing medicines, such synthetic insulin, which has largely replaced the use of animal pancreases in the manufacture of drugs used by diabetics to regulate their blood sugar levels.

To date, such recombinant DNA technology has used only natural amino acids, which limits the possible functions of the resulting protein products. The ability to insert Uaas could dramatically expand the possible uses of such technology, but one major barrier has limited the use of Uaas: only a single Uaa at a time could be incorporated into a protein.

To insert the instructions for including a Uaa in a bacterium’s genetic code, Wang and his colleagues exploited stop codons, special sequences of code in a protein’s genetic blueprint. During protein production, stop codons tell the cellular machinery to stop adding amino acids to the sequence that forms backbone of the protein’s structure.

In 2001, Wang and his colleagues modified the genetic sequence of the bacteria Escherichia coli to selectively include a stop codon and introduced engineered molecules inside the bacteria, which surgically insert a Uaa at the stop codon. This trained the bacteria to produce proteins with the Uaa incorporated in their backbone.

The problem was that another biological actor, a protein known as release factor 1 (RF1), would stop the production of a Uaa-containing protein too early. Although scientists could insert stop codons for Uaas at multiple places along genetic sequence, the release factor would cut the protein off at the first stop codon, preventing production of long proteins containing multiple Uaas.

“To really make use of this technology, you want to be able to engineer proteins that contain unnatural amino acids at multiple sites, and to produce them in high efficiency,” Wang said. “It was really promising, but, until now, really impractical.”

In their new paper, the Salk researchers and their collaborators at the University of California, San Diego described how they got around this limitation. Since RF1 hindered production of long Uaa-containing proteins, the scientists removed the gene that produces RF1. Then, because E. Coli dies when the RF1 gene is deleted, they altered production of an alternative actor, release factor 2 (RF2), so that it could rescue the engineered bacterium.

The result was a strain of bacteria capable of efficiently producing proteins containing Uaas at multiple places. These synthetic molecules hold promise for the development of drugs with biological functions far beyond what is possible with proteins that include only naturally occurring amino acids. They may also serve as the basis for manufacturing everything from industrial solvents to biofuels, possibly helping to address the economic and environmental concerns associated with petroleum-based manufacturing and transportation.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to produce a viable strain of bacteria capable of this,” Wang said. “We still have a ways to go, but this makes the possibility of using unnatural amino acids in biological engineering far closer to being reality.”

The research was funded by the Beckman Young Investigator Program, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the March of Dimes Foundation, the Mary K. Chapman Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Pioneer Fellowship, the Ray Thomas Edwards Foundation and the Searle Scholar Program.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu