December 21, 2017

Salk researchers uncover mechanism for how blood cells mature and specialize—and why errors can sometimes lead to leukemia

LA JOLLA—Like an actor who excels at both comedy and drama, proteins also can play multiple roles. Uncovering these varied talents can teach researchers more about the inner workings of cells. It also can yield new discoveries about evolution and how proteins have been conserved across species over hundreds of millions of years.

In a new finding, a team of investigators from the Salk Institute has uncovered in mouse cells a previously unknown job for a protein called nup98. In addition to helping control the movement of molecules in and out of the nucleus of the cell, they found that it also helps direct the development of blood cells, enabling immature blood stem cells to differentiate into many specialized mature cell types. Further, they discovered the mechanism by which—when perturbed—this differentiation process can contribute to the formation of certain types of leukemia. The findings are published in Genes & Development.

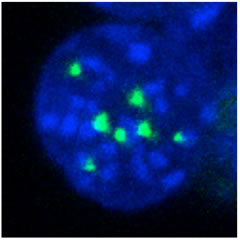

Credit: Salk Institute

“This research was really a tour de force,” says Martin Hetzer, Salk’s Chief Science Officer and the study’s senior author. “Tobias Franks, my postdoctoral researcher at the time and the paper’s first author, used an approach that combined genomics, proteomics, and cell biology. This model wasn’t easy to study, and he developed some very clever techniques in the lab to answer these questions.”

For years, Hetzer’s lab has focused on a class of proteins called nucleoporins (nups for short), which are part of the nuclear pore complex. This complex regulates traffic between the nucleus of the cell, where the genetic material is located, and the cytoplasm, which contains other cellular structures. There are about 30 proteins in the nucleoporin family, and they carry out a number of different functions in addition to forming the nuclear pore. Several of them are known to act as transcription factors: This means they help to regulate when and how genes get translated into proteins.

The finding that nup98 has this additional function was not entirely unexpected. Earlier research from Hetzer’s lab had found that it plays a role in gene regulation in other cell types. But the team didn’t know about its function in hematopoietic (blood) cells.

In addition, until now the mechanism of how nup98 regulates transcription was not known. The investigators found that it acts through a link with a protein complex called Wdr82-Set1/COMPASS, which is part of the cell’s epigenetic machinery. “This epigenetic process helps to control when genes are transcribed into proteins and when transcription is blocked,” says Hetzer, who also holds the Jesse and Caryl Phillips Foundation Chair.

Another thing that was different about this study is that it was done in mouse cells rather than simpler model organisms like yeast and fruit flies. “This is the first mechanistic insight of how one of these nup proteins works in mammals,” Hetzer adds. “We have only touched the surface here in uncovering how this evolutionarily conserved mechanism works in mammalian cells.” Future work in his lab will extend the study of nup98 to primates and humans.

While Hetzer has no immediate plans to pursue their findings as an avenue for developing leukemia drugs, he says it’s likely that others may pick up on this aspect of the research. Disruption of the cell differentiation process that contributes to leukemia results from a single gene fusion, when two parts of chromosomes that are not meant to act on each other become linked. He says that cancers driven by a single genetic change like this have proven easier to block with drugs than cancer driven by multiple genetic alterations.

The other authors were Asako McCloskey, Maxim Shokirev, Chris Benner, and Annie Rathore of Salk. Benner is also affiliated with the University of California, San Diego.

This work was funded by the Razavi Newman Integrative Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facility of the Salk Institute, the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, and the Helmsley Trust.

JOURNAL

Genes & Development

AUTHORS

Tobias M. Franks, Asako McCloskey, Maxim Shokirev, Chris Benner, Annie Rathore and Martin W. Hetzer

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge.