August 25, 2016

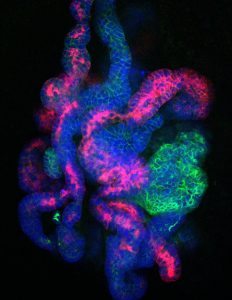

Salk researchers have succeeded in, for the first time, creating kidney progenitor cells that survive in the lab

Salk researchers have succeeded in, for the first time, creating kidney progenitor cells that survive in the lab

Click here for a high-resolution image

Credit: Salk Institute

LA JOLLA—Salk Institute scientists have discovered the holy grail of endless youthfulness—at least when it comes to one type of human kidney precursor cell. Previous attempts to maintain cultures of the so-called nephron progenitor cells often failed, as the cells died or gradually lost their developmental potential rather than staying in a more medically useful precursor state.

But by using a three-dimensional culture and a new mixture of supporting molecules, Salk researchers have successfully suspended the cells early in their development. Such early-stage kidney cells could be used to grow replacement kidney tissue in order to study the organ as well as treat disease.

“We provide a proof-of-principle for how to make and maintain unlimited numbers of precursor kidney cells,” says Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, professor in Salk’s Gene Expression Laboratory. “Having a supply of these cells could be a starting point to grow functional organs in the laboratory as well as a way to begin applying cell therapy to kidneys with malfunctioning genes.” The work was published in Cell Stem Cell on August 25, 2016.

Nephron progenitor cells (NPCs), at least in humans, normally only exist during a brief stage of embryonic development. The cells go on to form nephrons, the functional units of the kidney, responsible for filtering the blood and excreting urine. But adults have no remaining NPCs to grow new kidney tissue after damage or disease. Generating NPCs in the lab, scientists believe, will offer a new way to study kidney development and eventually treat kidney diseases.

Click here for a high-resolution image

Credit: Salk Institute

Previously, other groups of scientists have used induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to make NPC-like cells. “Those approaches take a long time, it is difficult to isolate a pure population, and the NPC-like cells are still transient,” says Zhongwei Li, a research associate in the Izpisua Belmonte lab and co-first author of the new paper. In those cases, the NPCs often matured into adult kidney cells in a manner of days, leaving no steady population of progenitor cells to study.

First working with NPCs directly isolated from mouse embryos, Izpisua Belmonte, Li and collaborators worked to develop methods that would keep the NPCs in their usually transient, progenitor state. They discovered that if they maintained the cells in a three-dimensional culture, rather than a flat dish, and used a new mixture of signaling molecules, they could maintain the NPCs for more than 15 months. They went on to show that the cells—when moved to new conditions—could then be coaxed to develop into functional nephron-like structures both in the lab or when transplanted into animals.

Next, the team used both human embryonic NPCs and human NPCs generated from stem cells to tweak the protocol for human use. Again, they were able to maintain the NPCs long term.

“The 3D culture strategy used in our study can potentially be applied to other lineage progenitors for efficient formation of tissue organoids,” says co-first author Jun Wu, Salk research associate.

Click here for a high-resolution image

Credit: Salk Institute

Aside from a regenerative therapy to replace ailing organs, the scientists add that the NPCs could be used to model diseases in the lab. By introducing disease related mutations to the cells, researchers could study the onset and progression of the disease and gain new insights into the disease as well as screen and discover new treatment drugs.

Next, the researchers would like to investigate how to culture the other types of progenitor cells that are required for a full kidney, in addition to the nephrons formed by NPCs. “There are several progenitor cells that work together to make a whole organ,” adds co-first author Toshikazu Araoka, Salk research associate. “If we can culture the other progenitor cells as well, we’ll be closer to building a transplantable kidney.”

Other researchers on the study were Hsin-Kai Liao, Mo Li, Min-Zu Wu, Isao Tamura, Yun Xia, Ergin Beyret, and Concepcion Rodriguez Esteban of the Salk Institute; Marta Lazo and Josep M. Campistol of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona; Bing Zhou and Yinghui Sui of the University of California, San Diego; Taji Matsusaka of Tokai University School of Medicine; Ira Pastan of the National Cancer Institute; Isabel Guillen and Pedro Guillen of Clinica Cemtro in Madrid.

The work and the researchers involved were supported by grants from the Kyoto University Foundation, the Nagai Foundation Tokyo, the Kidney Foundation Japan, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, a Catharina Foundation fellowship, the Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM), Fundacion Dr. Pedro Guillen, The G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and The Moxie Foundation.

JOURNAL

Cell Stem Cell

AUTHORS

Zhongwei Li, Toshikazu Araoka, Jun Wu, Hsin-Kai Liao, Mo Li, Marta Lazo, Bing Zhou, Yinghui Sui, Min-Zu Wu, Isao Tamura, Yun Xia, Ergin Beyret, Taiji Matsusaka, Ira Pastan, Concepcion Rodriguez Esteban, Isabel Guillen, Pedro Guillen, Josep M. Campistol, Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge.