February 28, 2010

LA JOLLA, CA—The first order of business for any fledgling plant embryo is to determine which end grows the shoot and which end puts down roots. Now, researchers at the Salk Institute expose the turf wars between two groups of antagonistic genetic master switches that set up a plant’s polar axis with a root on one end and a shoot on the other.

“In what is arguably the most important decision for a plant, setting up the root/shoot axis, occurs during the early embryonic stages,” says the study’s lead author Jeffrey A. Long, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory. “A tightly controlled balancing act between two groups of transcriptions factors ensures that they stay where they belong and don’t get into each other’s way.”

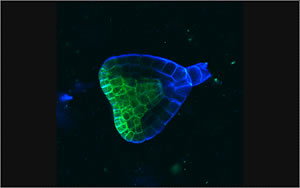

During plant embryogenesis microRNAs, labeled green, play an important part in the tightly orchestrated choreography that determines what goes up and what goes down. They ensure that HD-ZIP III genes are only expressed in the shoot meristem, which gives rise to all the above-ground portions of a plant.

Image: Courtesy of Zachary R. Smith, Salk Institute for Biological Studies

Plant embryogenesis establishes a very simple structure that contains two stem cell populations: the shoot meristem, which will give rise to all the “above-ground” organs such as the stem, the leaves and the flowers, and is the site of photosynthesis; and the root meristem, which gives rise to the root system, which lies below the ground and provides water and nutrients to the plant.

“Since plant stem cells ultimately give rise to all edible parts of plants understanding how their fate and function are regulated can be directly applied to modify the architecture of plants and to increase the yields of agriculturally important crops,” says Long.

The Salk researchers’ findings are published in the Feb. 28, 2010 advance online edition of the journal Nature.

“This work shows how genes interact in complex ways to establish organs along the root-shoot axis,” said Susan Haynes, Ph.D., who oversees developmental biology grants at the NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences. “The study reveals important parallels with the gene networks that coordinate organ formation in animal embryos, and helps us understand the critical mechanisms that guide normal development.”

While investigating why a defective TOPLESS gene messes with a plant’s basic architecture-mutant embryos develop into a seedling topped with a second root instead of a stem with leaves-Long and his team discovered functional TOPLESS codes for a repressor protein that inactivates genes that otherwise would cause root development in the shoot area of the plant.

In the current study Zachery R. Smith, a graduate student in Long’s laboratory, discovered that these fate-transforming genes are actually two familiar characters: the genes PLETHORA 1 and 2 had been known to act as master regulators that determine the identity of the root meristem.

“Without TOPLESS to keep them turned off, however, these two transcription factors are free to impose their will on the top half of the plant embryo causing the development of a second root instead of a shoot,” explains Smith.

With the “below-ground” hierarchy worked out, the question of how the identity of the shoot meristem is determined was still unanswered. Trying to unearth the missing master regulators of shoot development, Smith searched trough tens of thousands of mutant plants, till he hit on a member of the CLASS III HD-ZIP transcription factors, known as PHABULOSA, that fit the bill.

When the Salk researchers forcefully expressed members of the CLASS III HD-ZIP family in the traditional territory of the PLETHORA duo, it transformed the root into a shoot, resulting in a seedling with leaves on both ends. “Although it had been known that HD-ZIPs are involved in many aspects of plant polarity nobody had ever shown that they can transform a root pole into a shoot pole,” says Long. “This and other experiments showed that HD-ZIP III genes are master regulators of apical fate in early embryogenesis.”

Further studies revealed an antagonistic relationship between the PLETHORA and HD-ZIP III genes, both of which are under multiple modes of regulation that ensures proper spatial distribution and apical-basal patterning.

The work was supported in part by the Ray Thomas Edwards Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu