Announcer:

Welcome to the Salk Institute’s Where Cures Begin podcast, where scientists talk about breakthrough discoveries with your hosts, Allie Akmal and Brittany Fair.

Allie Akmal:

The Salk Institute was founded in 1960 by Jonas Salk, a physician scientist who in 1955 developed the first effective vaccine for polio, a highly contagious infection caused by a virus. He founded the Institute to be a place where scientists could conduct the kind of cutting-edge biological research that was key to his developing the polio vaccine.

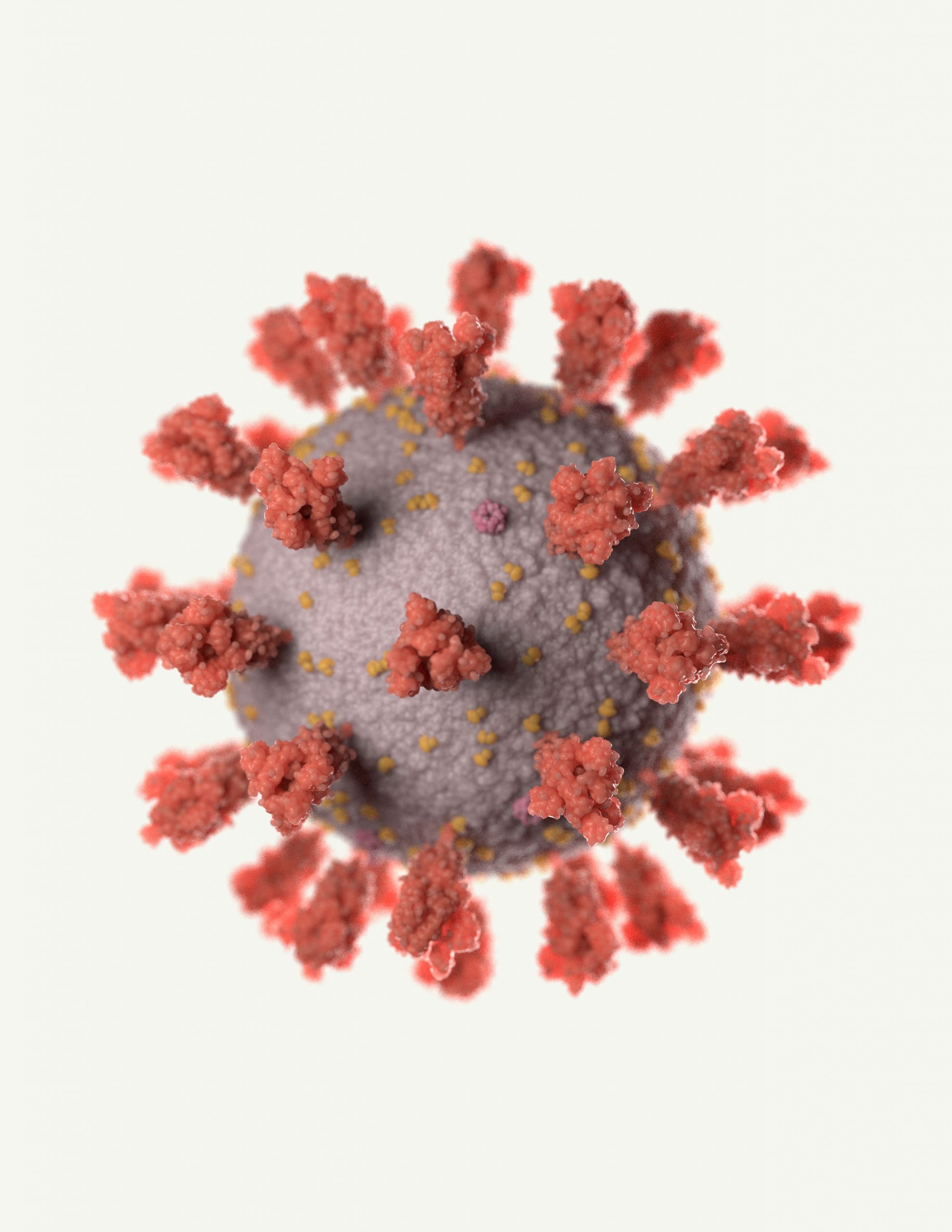

Today, the world is facing another frightening infection, the COVID-19 pandemic. So, we sat down remotely, of course, with some of our faculty who study infectious diseases, as well as our chief science officer for their perspectives on the current situation.

Martin Hetzer is Salk’s vice president and chief science officer. He is also a professor in Salk’s Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory. Professor Hetzer, what are your thoughts about lessons we can take away from the COVID-19 pandemic?

Martin Hetzer:

It reminds a lot of people of the the polio crisis in the late forties and early fifties, where we, like in the US actually, did have, what’s now referred to a social distancing where people in the summer periods didn’t go out, didn’t allow their kids to play. And so, it had a very similar feel. And I think it’s really remarkable, there’s a lot of articles being written about this now, how similar and how different those events were and also the 1918 flu epidemic is brought up a lot. But I think all those reflections really focus on and home in on is really the importance of science. I mean that’s really the one thing that persists throughout the decades and the centuries, that the only way to defeat diseases like COVID-19, polio, or keep things like influenza in check is science. To understand the underlying principles of infectious disease, and Salk does play an enormous role in many areas that are relevant to infectious disease.

Allie Akmal:

Professor Greg Lemke has been at Salk for many years and, in fact, knew Jonas Salk well. Professor Lemke, can you talk a little bit about polio, the disease for which Jonas Salk developed the vaccine in the 1950s.

Greg Lemke:

The polio virus, which is the virus that causes polio, the virus that Jonas dedicated many years of his life to combat, is an ancient virus. It has been with humankind for thousands and thousands of years, but we really didn’t experience serious polio epidemics until the beginning of the 20th century. The polio epidemics, they were seasonal. They would occur during the summer. They would wax and wane in the sense that some summers they’d be particularly bad. Some summers they weren’t quite so bad, but in each successive bad summer, it got worse and worse. So, by the time the Salk polio vaccine came online in mid 1950s, we had just experienced our very worst epidemic. So, the very worst epidemic here in the United States was in 1952. That killed several thousand people, made many more thousands of people sick on the consequences of polio.

Allie Akmal:

Susan Kaech is a professor in and the director of the NOMIS Center for Immunobiology and Microbial Pathogenesis. It is a research center within the Salk Institute that focuses on how we maintain health and immunity. NOMIS center faculty study infectious disease, inflammation, the immune system, autoimmune disease, cancer, and more. Professor Kaech, can you briefly describe how our immune system works?

Susan Kaech:

So, our immune system can be considered conceptually to be divided up into two major compartments. We have our innate immune system and we have our adaptive immune system. Our innate immune system essentially refers to cell types, such as macrophages, which can engulf and eat up pathogens or microbes in our bodies. Our adaptive immune system consists of our lymphocytes, our white blood cells, such as T cells or B cells. And these cells are called adaptive because they adapt to the pathogen upon the entry of the pathogen.

Allie Akmal:

So, the innate immune system is sort of like first responders who provide general first aid on the way to the hospital. Our adaptive immune system is like the specialists who show up later with more targeted treatments specific to the problem, but they can’t administer these therapies until they’ve had time to really figure out what ails the patient.

Susan Kaech:

So, our T cells exist in and our B cells exist in a naive state originally before the pathogen enters the body. But once the pathogen enters and they start to recognize that pathogen, then they start to adapt. They get activated and they expand in great numbers to fight that pathogen. And they have very specific receptors that can see those pathogens and try to target the infected cells. What we have been trying to understand is how does immune memory form and immune memory lies specifically within these adaptive immune cells, these memory T cells or these memory B cells that form after they’ve been exposed to and have responded to the pathogen.

Allie Akmal:

Professor Lemke’s work also focuses on how the immune system is controlled so that it responds enough to a threat, but doesn’t overreact as is being seen in some cases of COVID-19.

Greg Lemke:

In our lab, we study a set of receptors on the surface of cells that do various jobs in the immune system, but one of their most important jobs is actually to turn the immune response off after that response has successfully dealt with a problem, like an infection with a virus. And you may have heard that one of the clinically, one of the important complications for patients who are in the midst of suffering with COVID-19 is that they can have an overreaction to the virus and they can experience something called a cytokine storm. And that cytokine storm can cause a lot of problems for the patient and can actually make the disease worse. So, our lab actually studies how the cytokine response of immune cells is regulated. And as I said, we work on a set of receptors whose job is to control that spot, sort of make it reasonable enough so that you can fight the infection, but not too severe that you have the problems with the cytokines.

Allie Akmal:

Any final thoughts from you all related to COVID-19. Professor Lemke?

Greg Lemke:

Um, I think it’s important for everyone to know that scientists right now, um, are chaffing at this current situation. And we are really ready to hit the ground running, you know, to go full guns once we’re able to get back into the lab. And we’re really looking forward to that.

Allie Akmal:

Professor Kaech?

Susan Kaech:

As we’ve been seeing the outbreaks of measles and other infections, that really just, there’s no reason for them to be occurring other than the fact that fewer people are maintaining normal vaccine regimen. And so therefore we’re losing the herd immunity that protects our population as a whole. I think in one outcome of this would be to really understand and appreciate the importance of vaccines and, and not just from a personal perspective, but from a society perspective, the whole reason we’re living in quarantine in your shelter-in-place right now is not necessarily to protect us it’s to protect others in our society. So that those that are more vulnerable will not get exposed as much and therefore may not die because they got exposed, got infected and had a severe outcome.

Scientifically, it’s been a very interesting time to see and really demonstrate to the public how quickly science can move forward. If you think about it’s literally just a few months ago, when this virus was first discovered, it was sequenced within a very short period of time. That’s an already, there’ve been dozens of research publications published. I hope people will appreciate how much knowledge has been gained in such a short period of time due to advances in technology and in data exchange, computational analyses and medical knowledge. There’s maximal exchange of information. And so, I think that that should offer a lot of hope, but I think this has just been very positive, underlying aspect to the situation that we’re in.

Allie Akmal:

Professor Hetzer?

Martin Hetzer:

So very much in the spirit of Jonas Salk, we believe that foundational basic research is really the only way to mitigate the impact of crises such as COVID-19, but also to prevent it in the future and learn how to better deal with it when the next epidemic will hit us. And so, we’re well positioned to study the underlying principles of infectious disease.

Allie Akmal:

Thank you everyone for your insights and, listeners, Salk is in the process of tackling the SARS-CoV-2 virus in a number of ways. To learn more about our COVID-19 research visit salk.edu/coronavirus. Please stay well.

Announcer:

Join us next time for more cutting-edge Salk science. At Salk, world-renowned scientists work together to explore big bold ideas from cancer to Alzheimer’s aging to climate. Where Cures Begin is a production of the Salk Institute’s Office of Communications.